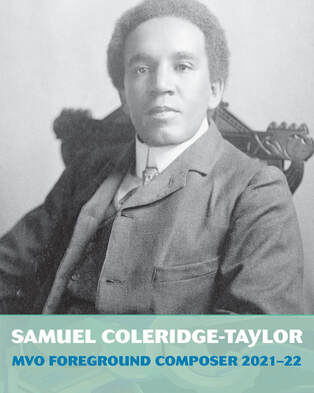

MVO FOREGROUND COMPOSER 2021-2022: SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

Every year, beginning in the 2021-22 season, the Mississippi Valley Orchestra focuses its program on an underrepresented composer by performing the composer's works throughout the season, bringing them to the "foreground" for audience to rediscover their neglected musical geniuses. For Season 2021-2022, we feature Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Read more about the composer and enjoy excerpts from MVO's performances below.

|

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in London in 1875, his mother English, his father from Sierra Leone. He grew up in Croydon, Surrey, and began learning the violin at the age of 5, with his mother’s father as his first teacher. At 15, he began studying violin at the Royal College of Music in London. In his third year he changed his focus to composition, studying with Charles Villiers Stanford. He became a professional musician, professor, and conductor—and then a wildly popular composer. Currently, Coleridge-Taylor may be best known for his fame during his short lifetime (37 years): only Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah were as popular as his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. Also, inspired by three tours of the United States—which increased his interest in his father’s heritage—and by Johannes Brahms, and Antonín Dvořák, he developed European classical music with influences from traditional African music.

|

Hiawatha: Longfellow’s Literary and Ethnographic Playground

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

Hugely popular, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha was published in 1855 and sold 30,000 copies in six months. Capturing European-American readers’ imaginations, the poem also generated numerous parodies, including Lewis Carroll’s “Hiawatha’s Photographing.” Carroll prefaced his much shorter poem with a condescending note about the trochaic meter Longfellow had chosen.

In an age of imitation, I can claim no special merit for this slight attempt at doing what is known to be so easy. Any fairly practised writer, with the slightest ear for rhythm, could compose, for hours together, in the easy running metre of The Song of Hiawatha. Having then distinctly stated that I challenge no attention in the following little poem to its merely verbal jingle, I must beg the candid reader to confine his criticism to its treatment of the subject.

These literary pranks should have been the least of Longfellow’s concerns considering the long-lasting impacts of the poem’s inaccurate representation of Native American communities. Although Longfellow asserted that the “Indian legends” that inspired the poem were authentic, his sources were confused at best. Henry R. Schoolcraft, a well-known American ethnographer at the time, published Algic Researches in 1839 after completing his work as an Indian agent—representing the United States government—with the Anishinaabe people in Michigan. Decades later, American folklorist Stith Thompson suggested that in Schoolcraft’s “many volumes of undigested material, material that was sometimes inaccurate but always rich with the poetic lore of the tribal mythologies,” Longfellow found a treasure trove of purportedly authentic Native American folk tales for his poem.

Initially, the name of the poem’s hero was to be Manabozho, after an Anishinaabe demi-god. Many folk tales of Manabozho’s heroic and less heroic acts exist. The complexity of the demi-god’s dual role as a culture hero and trickster was lost on Schoolcraft, however, and he interpreted Manabozho as ‘‘rather a monstrosity than a deity, displaying in strong colors far more of the dark and incoherent acts of a spirit of carnality than the benevolent deeds of a god. . . . His bravery, strength, wisdom, ‘high exploits,’ clash with his ‘low tricks.’” Longfellow was intrigued by the stories of Manabozho but was looking for a less troublesome hero to appeal to his predominantly white audience’s sensibilities. Based on Schoolcraft’s mistaken claim that Hiawatha was an alternative name for Manabozho, Longfellow, according to his daughter, Alice, “blended the supernatural deeds of the crafty sprite with the wise, noble spirit of the Iroquois national hero, and formed the character of Hiawatha.’’

A far cry from the poem’s depiction of a “white man’s Indian,” complacently accepting the arrival of white people and Christianity, in historical reality, Hiawatha was a sixteenth-century leader of the Mohawk tribe—from the region of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River—and co-founder of the League of Five Nations, a precolonial confederacy that ushered in a period of unprecedented peace for the Iroquois tribes.

Schoolcraft is not the source of all of the poem’s fabrications. Longfellow took several artistic liberties in character representation and also character creation. Minnehaha, Hiawatha’s fictional lover in the poem, from the competing Dakota tribe, was purely his invention. In his notes in the first edition of The Song of Hiawatha, the poet quoted Mary H. Eastman's description of Minnehaha Falls, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, from her book Dahcotah; or, Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling (1849): “The scenery about Fort Snelling is rich in beauty. The Falls of St. Anthony are familiar to travellers, and to readers of Indian sketches. Between the fort and these falls are the ‘Little Falls,’ forty feet in height, on a stream that empties into the Mississippi. The Indians call them Mine-hah-hah, or ‘laughing waters.’” But in 1920, American geologist and archaeologist Dr. Warren Upham clarified in Minnesota Geographic Names that “The common Sioux word for waterfall is ‘haha,’ which they applied to the falls of St. Anthony, to Minnehaha, and in general to any waterfall or cascade. To join the words ‘minne,’ water, and ‘haha,’ a fall, seems to be the suggestion of white men, which thereafter came into use among the Indians.”

These discrepancies were not mentioned in Longfellow’s notes on the poem. But his invented intertribal courtship cemented itself in the public consciousness. The naming of the two adjacent main roads Hiawatha and Minnehaha Avenues within the Longfellow neighborhood of south Minneapolis, which contains the falls, is only one of numerous examples of Hiawatha-inspired place names throughout the Midwest.

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

Hugely popular, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha was published in 1855 and sold 30,000 copies in six months. Capturing European-American readers’ imaginations, the poem also generated numerous parodies, including Lewis Carroll’s “Hiawatha’s Photographing.” Carroll prefaced his much shorter poem with a condescending note about the trochaic meter Longfellow had chosen.

In an age of imitation, I can claim no special merit for this slight attempt at doing what is known to be so easy. Any fairly practised writer, with the slightest ear for rhythm, could compose, for hours together, in the easy running metre of The Song of Hiawatha. Having then distinctly stated that I challenge no attention in the following little poem to its merely verbal jingle, I must beg the candid reader to confine his criticism to its treatment of the subject.

These literary pranks should have been the least of Longfellow’s concerns considering the long-lasting impacts of the poem’s inaccurate representation of Native American communities. Although Longfellow asserted that the “Indian legends” that inspired the poem were authentic, his sources were confused at best. Henry R. Schoolcraft, a well-known American ethnographer at the time, published Algic Researches in 1839 after completing his work as an Indian agent—representing the United States government—with the Anishinaabe people in Michigan. Decades later, American folklorist Stith Thompson suggested that in Schoolcraft’s “many volumes of undigested material, material that was sometimes inaccurate but always rich with the poetic lore of the tribal mythologies,” Longfellow found a treasure trove of purportedly authentic Native American folk tales for his poem.

Initially, the name of the poem’s hero was to be Manabozho, after an Anishinaabe demi-god. Many folk tales of Manabozho’s heroic and less heroic acts exist. The complexity of the demi-god’s dual role as a culture hero and trickster was lost on Schoolcraft, however, and he interpreted Manabozho as ‘‘rather a monstrosity than a deity, displaying in strong colors far more of the dark and incoherent acts of a spirit of carnality than the benevolent deeds of a god. . . . His bravery, strength, wisdom, ‘high exploits,’ clash with his ‘low tricks.’” Longfellow was intrigued by the stories of Manabozho but was looking for a less troublesome hero to appeal to his predominantly white audience’s sensibilities. Based on Schoolcraft’s mistaken claim that Hiawatha was an alternative name for Manabozho, Longfellow, according to his daughter, Alice, “blended the supernatural deeds of the crafty sprite with the wise, noble spirit of the Iroquois national hero, and formed the character of Hiawatha.’’

A far cry from the poem’s depiction of a “white man’s Indian,” complacently accepting the arrival of white people and Christianity, in historical reality, Hiawatha was a sixteenth-century leader of the Mohawk tribe—from the region of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River—and co-founder of the League of Five Nations, a precolonial confederacy that ushered in a period of unprecedented peace for the Iroquois tribes.

Schoolcraft is not the source of all of the poem’s fabrications. Longfellow took several artistic liberties in character representation and also character creation. Minnehaha, Hiawatha’s fictional lover in the poem, from the competing Dakota tribe, was purely his invention. In his notes in the first edition of The Song of Hiawatha, the poet quoted Mary H. Eastman's description of Minnehaha Falls, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, from her book Dahcotah; or, Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling (1849): “The scenery about Fort Snelling is rich in beauty. The Falls of St. Anthony are familiar to travellers, and to readers of Indian sketches. Between the fort and these falls are the ‘Little Falls,’ forty feet in height, on a stream that empties into the Mississippi. The Indians call them Mine-hah-hah, or ‘laughing waters.’” But in 1920, American geologist and archaeologist Dr. Warren Upham clarified in Minnesota Geographic Names that “The common Sioux word for waterfall is ‘haha,’ which they applied to the falls of St. Anthony, to Minnehaha, and in general to any waterfall or cascade. To join the words ‘minne,’ water, and ‘haha,’ a fall, seems to be the suggestion of white men, which thereafter came into use among the Indians.”

These discrepancies were not mentioned in Longfellow’s notes on the poem. But his invented intertribal courtship cemented itself in the public consciousness. The naming of the two adjacent main roads Hiawatha and Minnehaha Avenues within the Longfellow neighborhood of south Minneapolis, which contains the falls, is only one of numerous examples of Hiawatha-inspired place names throughout the Midwest.

|

|

|

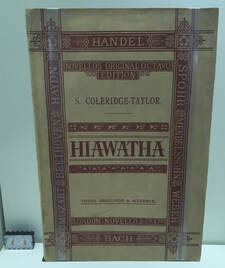

In March 2022, during a visit to the National Museum of African American History & Culture, MVO violinist Linda Ruetz found an edition of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha on display.

In March 2022, during a visit to the National Museum of African American History & Culture, MVO violinist Linda Ruetz found an edition of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha on display.

Hiawatha’s Musical Fans: Dvořák and Coleridge-Taylor

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

Not long after the publication of Hiawatha, German-born American composer Robert August Stoepel approached Longfellow with his piece Hiawatha: A Romantic Symphony. In his journal, Longfellow wrote that the music was “beautiful and striking; particularly the wilder parts.” After reading a Czech translation of the poem in the 1870s, Antonín Dvořák dreamed of composing a Hiawatha opera. In an 1893 interview with the New York Herald at the premiere of his Symphony No. 9, “From the New World,” Dvořák identified the poem as the inspiration for the symphony’s second and third movements and mentioned plans for the opera.

The second movement is an Adagio. But it is different to the classic works in this form. It is in reality a study or a sketch for a longer work, either a cantata or an opera which I purpose writing, and which will be based upon Longfellow's "Hiawatha." I have long had the idea of someday utilizing that poem. I first became acquainted with it about thirty years ago through the medium of a Bohemian translation. It appealed very strongly to my imagination at that time, and the impression has only been strengthened by my residence here. The scherzo of the symphony was suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance, and is also an essay I made in the direction of imparting the local color of Indian character to music.

While Dvořák’s plans never came to fruition, he found other intriguing sources for American folk songs in African-American music. Harry Burleigh was an African-American pupil at the National Conservatory of Music in New York during the early 1890s who exposed Dvořák to multiple African-American spirituals. One particular example: “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” can be heard in the closing bars of the symphony’s first movement.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a young Anglo-African composer at the time, admired both men. He wrote: “Dvořák was my first musical love, and I have received more from his works than from anyone's, perhaps. I love the ‘open-air’ sound this music always has and the genuine simplicity which our modern music so often lacks.” On Burleigh, he later commented, “Everyone agrees that he is a splendid singer, and also—more rare—a splendid musician too.”

Coleridge-Taylor also found inspiration from Longfellow, just like Dvořák and Stoepel. In 1898, the Royal College of Music in London premiered the composer’s first cantata, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. A review of the performance by The Referee noted, “In Longfellow’s Indian ‘poem,’ a portion of which forms the text of the cantata, Mr. Taylor has found a subject in complete sympathy with his genius, and the very spirit of the Wild West seems to move in and give life to the strains in which the doings at the barbaric feast are told.” The combination of melodic mastery and the poem’s “barbaric” subject turned Coleridge-Taylor into an overnight sensation and garnered him several high-profile supporters.

Composer Edward Elgar, in his 40s at the time, was highly complimentary of the young Coleridge-Taylor. In a letter to the musical director of a festival at Gloucester, he advocated for a performance of Coleridge-Taylor’s work.

He is the coming man, I’m quite sure! He is only 22 or 23 but there is nothing immature or inartistic about his music. It is worth a great deal to me—I mean I value it very highly, because it is so original and often beautiful. Here is a real melodist at last...We are doing a short Cantata of his, ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast’; delightful stuff! Won’t that do for your Festival?... At any rate you keep your eye on the lad, and believe me, he is the man of the future in musical England.

The popularity of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast produced a high demand for more Hiawatha cantatas by Coleridge-Taylor, and he subsequently composed The Death of Minnehaha and Hiawatha’s Departure, creating a trilogy. Although Coleridge-Taylor traveled to America only after the trilogy was published, he was already drawn to the music of African-Americans. The overture to the trilogy, often performed as a stand-alone orchestral piece, quotes the spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” most likely heard by Coleridge-Taylor at a performance of Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers while they were touring Britain.

Following one too many festival performances of Hiawatha, Elgar became jealous of Coleridge-Taylor’s success. After hearing the overture to the trilogy in January 1900, he wrote to his friend, and Coleridge-Taylor’s publisher, August Jaeger: “I think you are right about C. Taylor—I was cruelly disillusioned by the overture to Hiawatha which I think really only ‘rot.’” Critics disagreed. In 1899, the Morning Post (London) had hailed the overture as “a very interesting work, full of fiery energy, scored with consummate art, and containing broadly melodious phrases.”

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

Not long after the publication of Hiawatha, German-born American composer Robert August Stoepel approached Longfellow with his piece Hiawatha: A Romantic Symphony. In his journal, Longfellow wrote that the music was “beautiful and striking; particularly the wilder parts.” After reading a Czech translation of the poem in the 1870s, Antonín Dvořák dreamed of composing a Hiawatha opera. In an 1893 interview with the New York Herald at the premiere of his Symphony No. 9, “From the New World,” Dvořák identified the poem as the inspiration for the symphony’s second and third movements and mentioned plans for the opera.

The second movement is an Adagio. But it is different to the classic works in this form. It is in reality a study or a sketch for a longer work, either a cantata or an opera which I purpose writing, and which will be based upon Longfellow's "Hiawatha." I have long had the idea of someday utilizing that poem. I first became acquainted with it about thirty years ago through the medium of a Bohemian translation. It appealed very strongly to my imagination at that time, and the impression has only been strengthened by my residence here. The scherzo of the symphony was suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance, and is also an essay I made in the direction of imparting the local color of Indian character to music.

While Dvořák’s plans never came to fruition, he found other intriguing sources for American folk songs in African-American music. Harry Burleigh was an African-American pupil at the National Conservatory of Music in New York during the early 1890s who exposed Dvořák to multiple African-American spirituals. One particular example: “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” can be heard in the closing bars of the symphony’s first movement.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a young Anglo-African composer at the time, admired both men. He wrote: “Dvořák was my first musical love, and I have received more from his works than from anyone's, perhaps. I love the ‘open-air’ sound this music always has and the genuine simplicity which our modern music so often lacks.” On Burleigh, he later commented, “Everyone agrees that he is a splendid singer, and also—more rare—a splendid musician too.”

Coleridge-Taylor also found inspiration from Longfellow, just like Dvořák and Stoepel. In 1898, the Royal College of Music in London premiered the composer’s first cantata, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. A review of the performance by The Referee noted, “In Longfellow’s Indian ‘poem,’ a portion of which forms the text of the cantata, Mr. Taylor has found a subject in complete sympathy with his genius, and the very spirit of the Wild West seems to move in and give life to the strains in which the doings at the barbaric feast are told.” The combination of melodic mastery and the poem’s “barbaric” subject turned Coleridge-Taylor into an overnight sensation and garnered him several high-profile supporters.

Composer Edward Elgar, in his 40s at the time, was highly complimentary of the young Coleridge-Taylor. In a letter to the musical director of a festival at Gloucester, he advocated for a performance of Coleridge-Taylor’s work.

He is the coming man, I’m quite sure! He is only 22 or 23 but there is nothing immature or inartistic about his music. It is worth a great deal to me—I mean I value it very highly, because it is so original and often beautiful. Here is a real melodist at last...We are doing a short Cantata of his, ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast’; delightful stuff! Won’t that do for your Festival?... At any rate you keep your eye on the lad, and believe me, he is the man of the future in musical England.

The popularity of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast produced a high demand for more Hiawatha cantatas by Coleridge-Taylor, and he subsequently composed The Death of Minnehaha and Hiawatha’s Departure, creating a trilogy. Although Coleridge-Taylor traveled to America only after the trilogy was published, he was already drawn to the music of African-Americans. The overture to the trilogy, often performed as a stand-alone orchestral piece, quotes the spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” most likely heard by Coleridge-Taylor at a performance of Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers while they were touring Britain.

Following one too many festival performances of Hiawatha, Elgar became jealous of Coleridge-Taylor’s success. After hearing the overture to the trilogy in January 1900, he wrote to his friend, and Coleridge-Taylor’s publisher, August Jaeger: “I think you are right about C. Taylor—I was cruelly disillusioned by the overture to Hiawatha which I think really only ‘rot.’” Critics disagreed. In 1899, the Morning Post (London) had hailed the overture as “a very interesting work, full of fiery energy, scored with consummate art, and containing broadly melodious phrases.”

|

|

|

Coleridge-Taylor’s African-American Supporters

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

The appeal of Coleridge-Taylor’s trilogy was not limited to elite British composers and critics. Within weeks of the premiere of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, Burleigh had sent a copy of the music to Mamie Hilyer, an African American pianist, and wife of Washington, D.C. lawyer Andrew Hilyer. The Hilyers quickly established the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, an organization of musicians of color looking to expose audiences to the composer’s works. Meanwhile, Coleridge-Taylor was rising to a level of prominence in the international Black community unprecedented for composers. In 1900, Coleridge-Taylor was the youngest delegate at the first Pan-African Conference. A formative experience for his views on racial issues, he formed close relationships with several delegates, including W.E.B. Du Bois, who was a rising star in his own right.

While Coleridge-Taylor was busy teaching, composing, and performing in England, the Society’s performances of Hiawatha were increasing the visibility of African-American musicians in Washington, D.C. The New York Times commented on a 1903 performance of Hiawatha at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church: “The concert opens up a field of interesting speculation as to the possibility of the colored people in the higher regions of music, and fully justifies the decision of the managers of the society to continue their work as a permanent organization.” Shortly after, the Hilyers organized the composer’s first American tour, in 1904. The tour included multiple performances of Hiawatha and an invitation to meet then-president Theodore Roosevelt. In preparation for the trip, the Hilyers sent Coleridge-Taylor a copy of Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, a literary work that the composer praised as "about the finest book I have ever read by a colored man, and one of the best by any author, white or black." The respect was mutual. In response to the composer’s premature death in 1912, Du Bois shared a memory of an early performance of Hiawatha that he attended around the time of the conference in 1900. In the essay “The Immortal Child,” he argued that the young composer viewed life as “neither meat nor drink,—it was creative flame; ideas, plans, melodies glowed within him.”

by Penelope Corbett, University of Minnesota Honors Student

The appeal of Coleridge-Taylor’s trilogy was not limited to elite British composers and critics. Within weeks of the premiere of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, Burleigh had sent a copy of the music to Mamie Hilyer, an African American pianist, and wife of Washington, D.C. lawyer Andrew Hilyer. The Hilyers quickly established the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, an organization of musicians of color looking to expose audiences to the composer’s works. Meanwhile, Coleridge-Taylor was rising to a level of prominence in the international Black community unprecedented for composers. In 1900, Coleridge-Taylor was the youngest delegate at the first Pan-African Conference. A formative experience for his views on racial issues, he formed close relationships with several delegates, including W.E.B. Du Bois, who was a rising star in his own right.

While Coleridge-Taylor was busy teaching, composing, and performing in England, the Society’s performances of Hiawatha were increasing the visibility of African-American musicians in Washington, D.C. The New York Times commented on a 1903 performance of Hiawatha at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church: “The concert opens up a field of interesting speculation as to the possibility of the colored people in the higher regions of music, and fully justifies the decision of the managers of the society to continue their work as a permanent organization.” Shortly after, the Hilyers organized the composer’s first American tour, in 1904. The tour included multiple performances of Hiawatha and an invitation to meet then-president Theodore Roosevelt. In preparation for the trip, the Hilyers sent Coleridge-Taylor a copy of Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, a literary work that the composer praised as "about the finest book I have ever read by a colored man, and one of the best by any author, white or black." The respect was mutual. In response to the composer’s premature death in 1912, Du Bois shared a memory of an early performance of Hiawatha that he attended around the time of the conference in 1900. In the essay “The Immortal Child,” he argued that the young composer viewed life as “neither meat nor drink,—it was creative flame; ideas, plans, melodies glowed within him.”

|

Penelope Corbett is a freshman at the University of Minnesota double majoring in Music and Psychology. She studies violin with Stephanie Arado in the School of Music, and her former teachers include Minnesota Orchestra members Natsuki Kumagai and Aaron Janse. In addition to playing with the University Symphony Orchestra, she is a member of the Honors Program, a Colin MacLaurin Fellow at Anselm House, and a research assistant in the Auditory Perception and Cognition Laboratory. In 2021, she placed first in the high school strings division of the Thursday Musical Scholarship Competition. Penelope is an enthusiastic promoter of music education and has taught violin to students from Stillwater Middle School and Folwell Community School in Minneapolis. In her free time, she enjoys going on walks with her standard poodle, Louis. To learn more from Penelope's research, please come to our concert on May 22, 2022 and join our pre-concert talk at 2:15 p.m. |